The Middle Oconee - January Snow

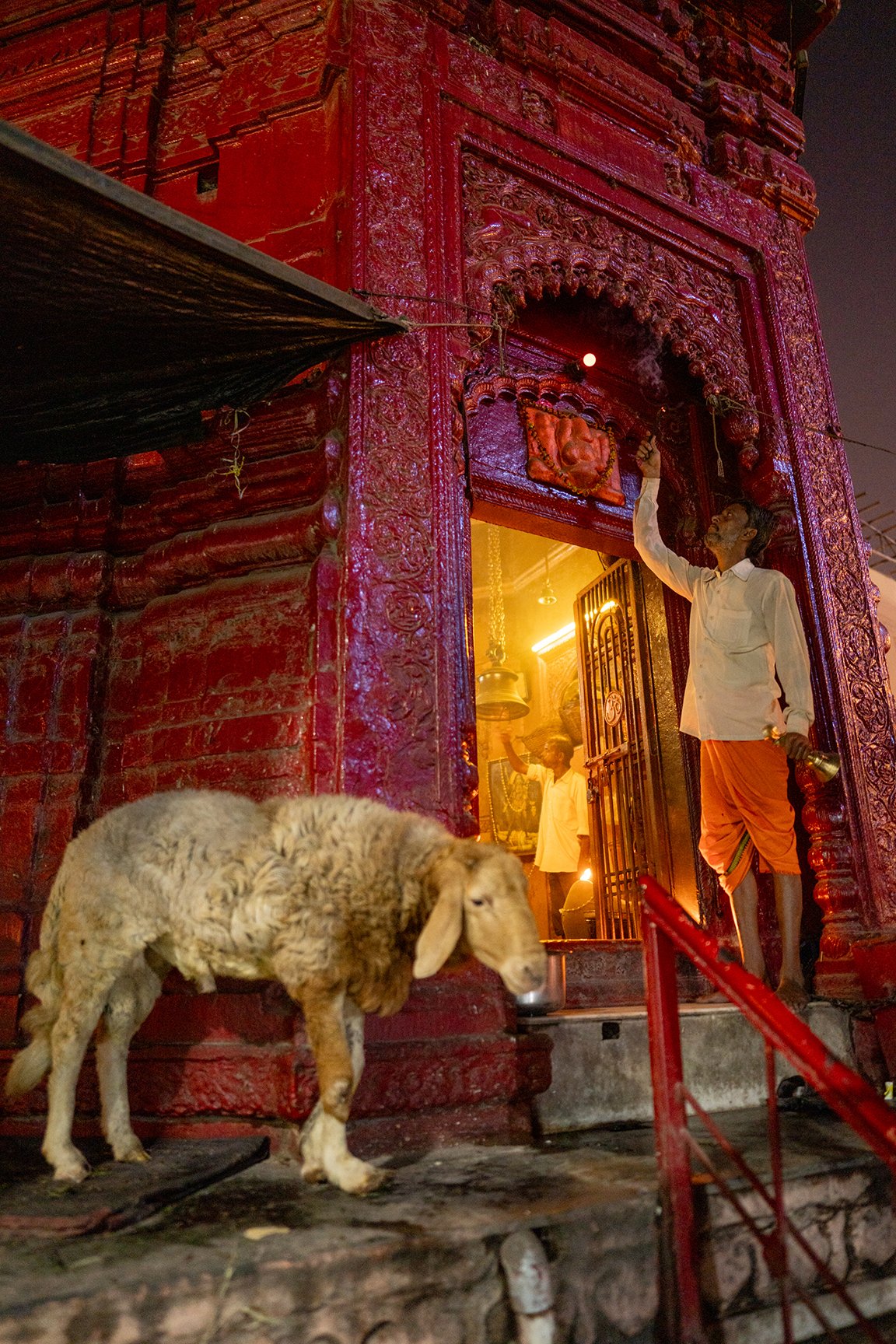

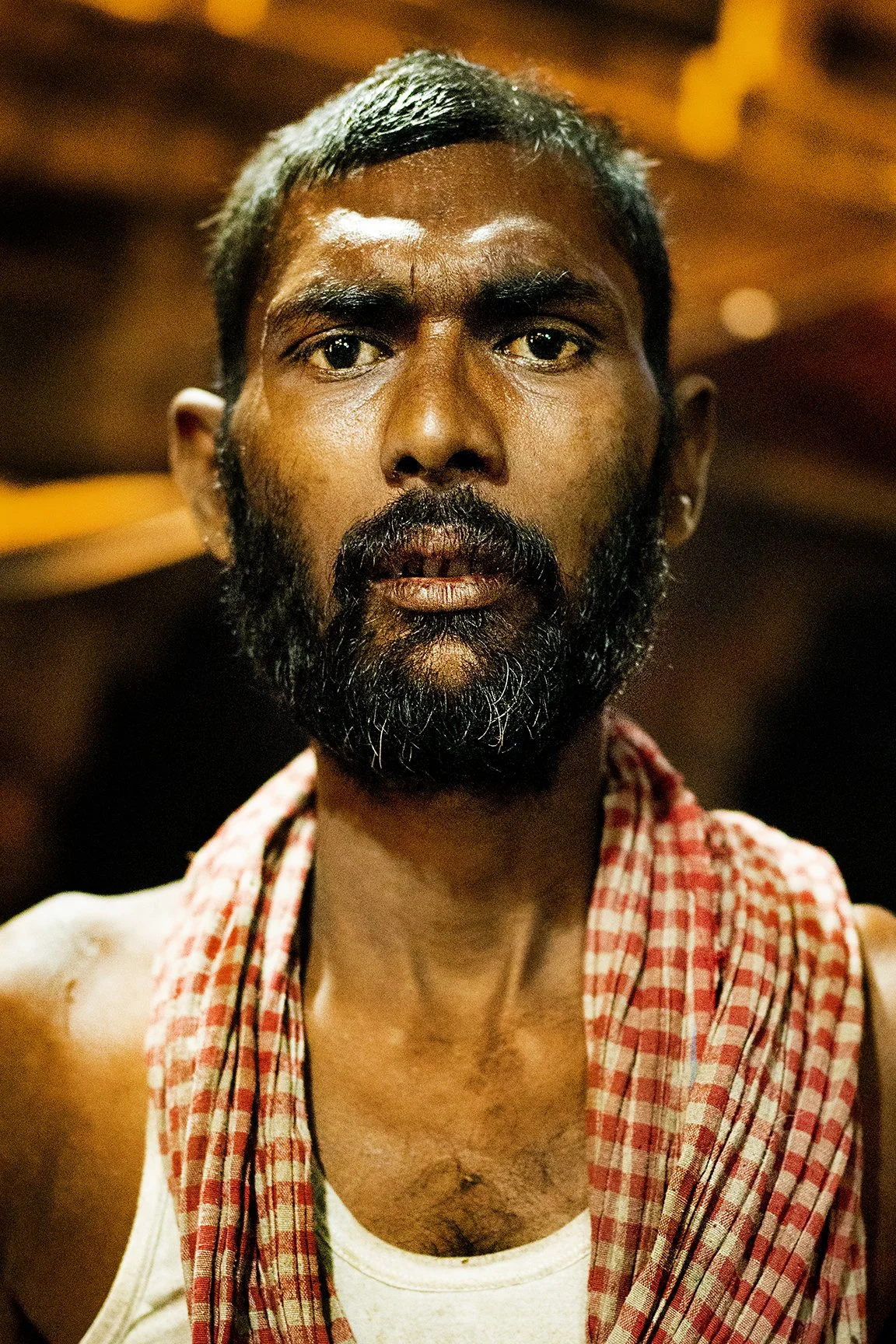

The Manikarnika Ghat - The Sacred Cremation Ground of Benares

The Manikarnika Ghat - The Sacred Cremation Ground of Benares

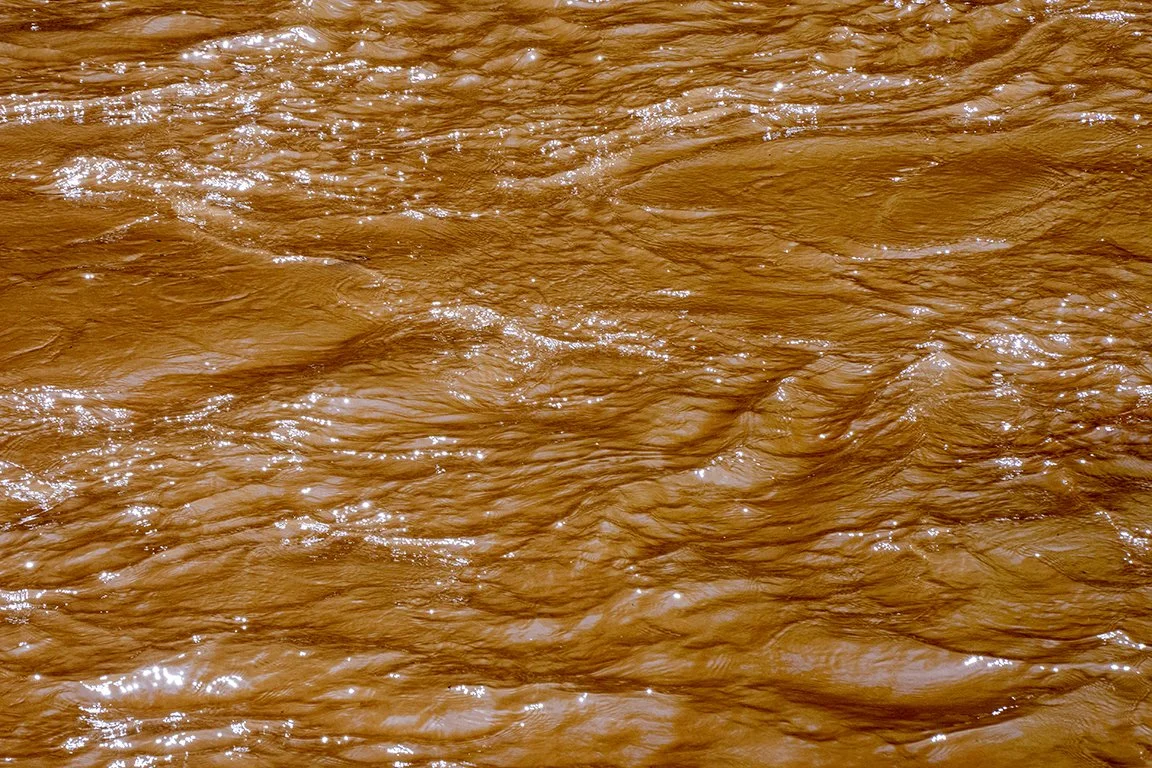

The Middle Oconee

The Middle Oconee

2025 Highlights

2025 Year in Review - Art, Travel, Gallery, Family and Friends.

25 Years with this amazing woman on 11//11/25.

I finished off last year by making this portrait of my daughters with a 4x5 View Camera.

I was commissioned to do a photography project on the Middle Oconee River by the Oconee River Landtrust. I spent the year visiting the river and watching it change through the seasons. I was lucky to catch it twice in the snow last winter.

We hosted poet Drew Lanham and musician T Hardy Morris at the gallery for a reading of Drew’s Poem Reason By Rot from the Murmur Trestle book.

Patterson Hood’s brilliant solo album Exploding Trees and Airplane Screams was released with the stunning album cover by the one and only Frances Thrasher. I was lucky to have a couple of portraits of Patterson inside the album.

Frances also directed and produced this stunning video for the song The Pool House.

I was finally able to put some time towards the sequel to Athens Potluck. I had photographed Parker Allen just before Covid and when I started it back up he chose Adam Wayton. It has been a really great experience meeting a new generation of Athens artist this year.

Adam Wayton working the bag.

The Ace Francisco Gallery started off a very busy year with an exhibition by Beth’s sister Louise Hall and our great friend Ceci Reynolds.

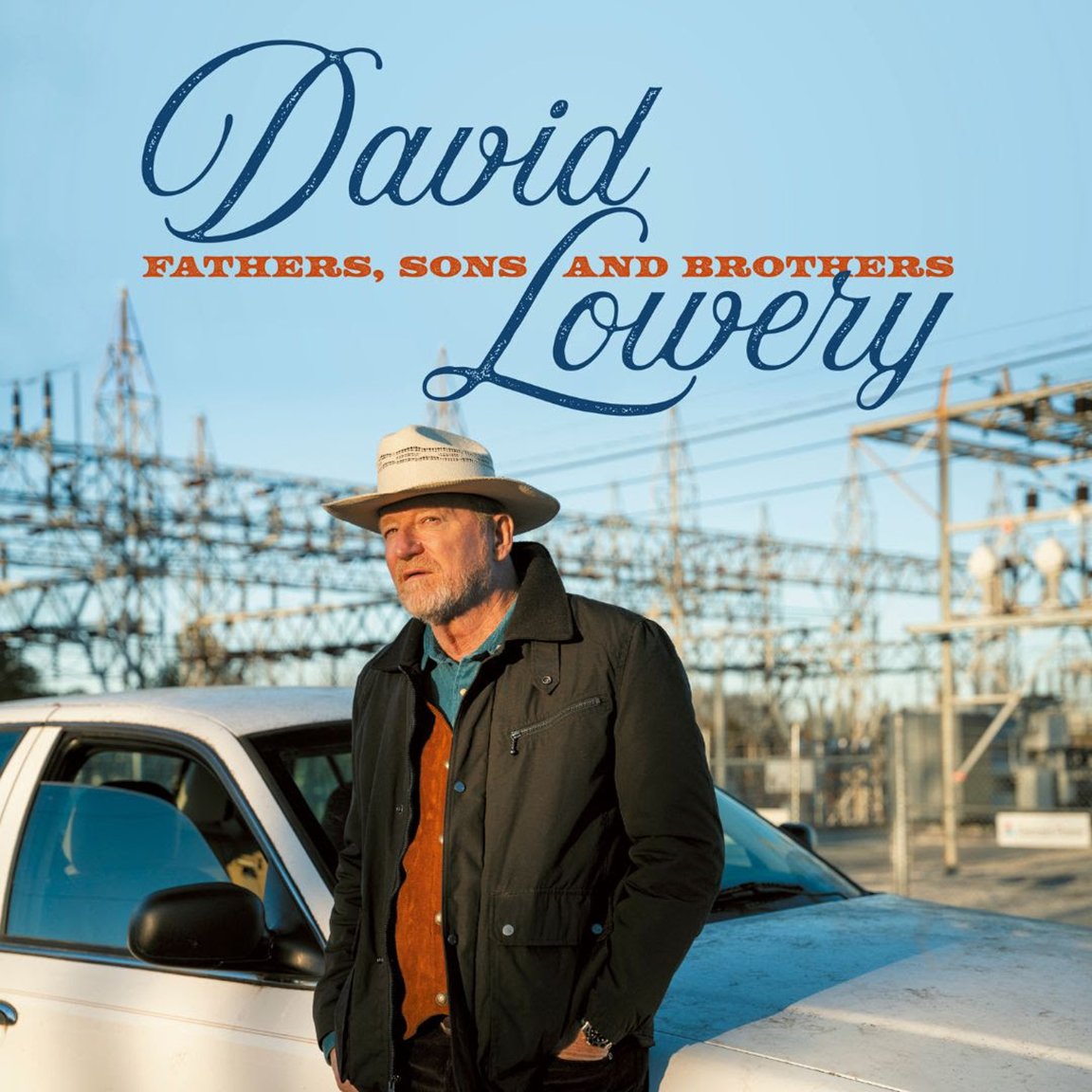

David Lowrey and Johnny Hickman, It was around the time of this photo shoot with Cracker that I realized I had been working with them for almost half of their time together as a band.

Cracker 2025

I am stoked and proud to have my portrait of David Lowery on the cover of his new solo album and to have about a dozen other images used throughout the design of the album.

Emi Lynn photographed with the 4x5 film camera. This project was one of the goals for 2025 that kind of got lost in the year with so many other things going on. Maybe it’ll get more attention in 2026.

The largest photograph I’ve ever had framed. This baby measures 7x11 feet and was installed at the 1785 Club over by Nuci’s Space.

Spring on the Middle Oconee River.

Our dear friends in Five Eight produced a killer new album and I had the chance to produce the video for the hit single Take Me To The Skatepark which we filmed at the beloved Skate Park of Athens which turned 20 years old last spring.

The Bell Hotel in downtown Athens is a design masterpiece.

I saw this amazing looking couple at the 40 Watt Club and they were kind enough to step outside for this portrait and yes that’s a tinfoil cowboy hat.

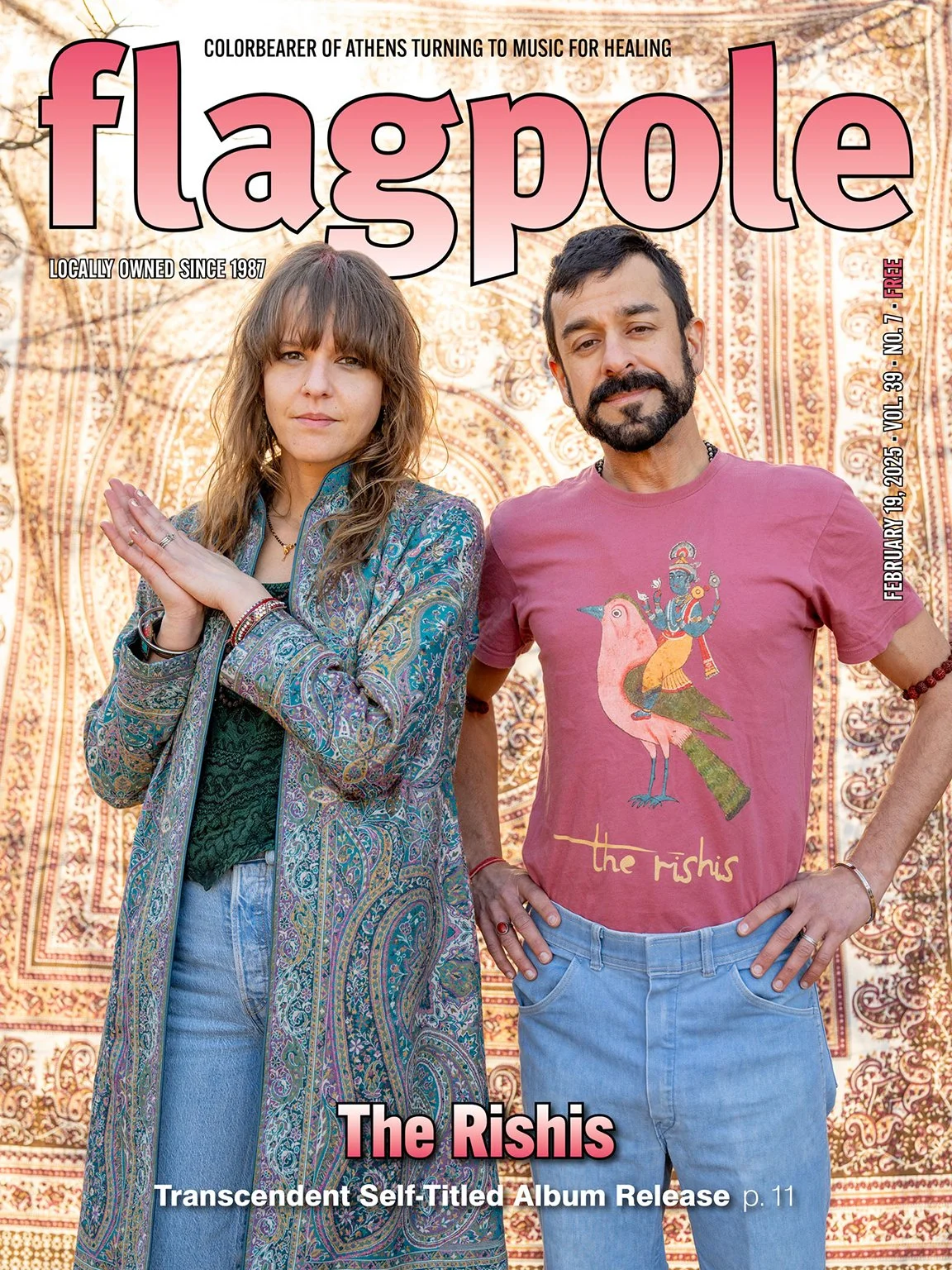

The Rishis for the cover of Flagpole.

Micheal White for his new album.

Sweet Will on the cover of the Flagpole. This one is a heart breaker.

Adam Wayton chose Viv Aweomse for the new project that I’m calling Athens House Party.

Viv and Oliver Domingo. Unlike Potluck I’ve been photographing the subject with the person that they are choosing for the project. These have been some of my favorite images for the project.

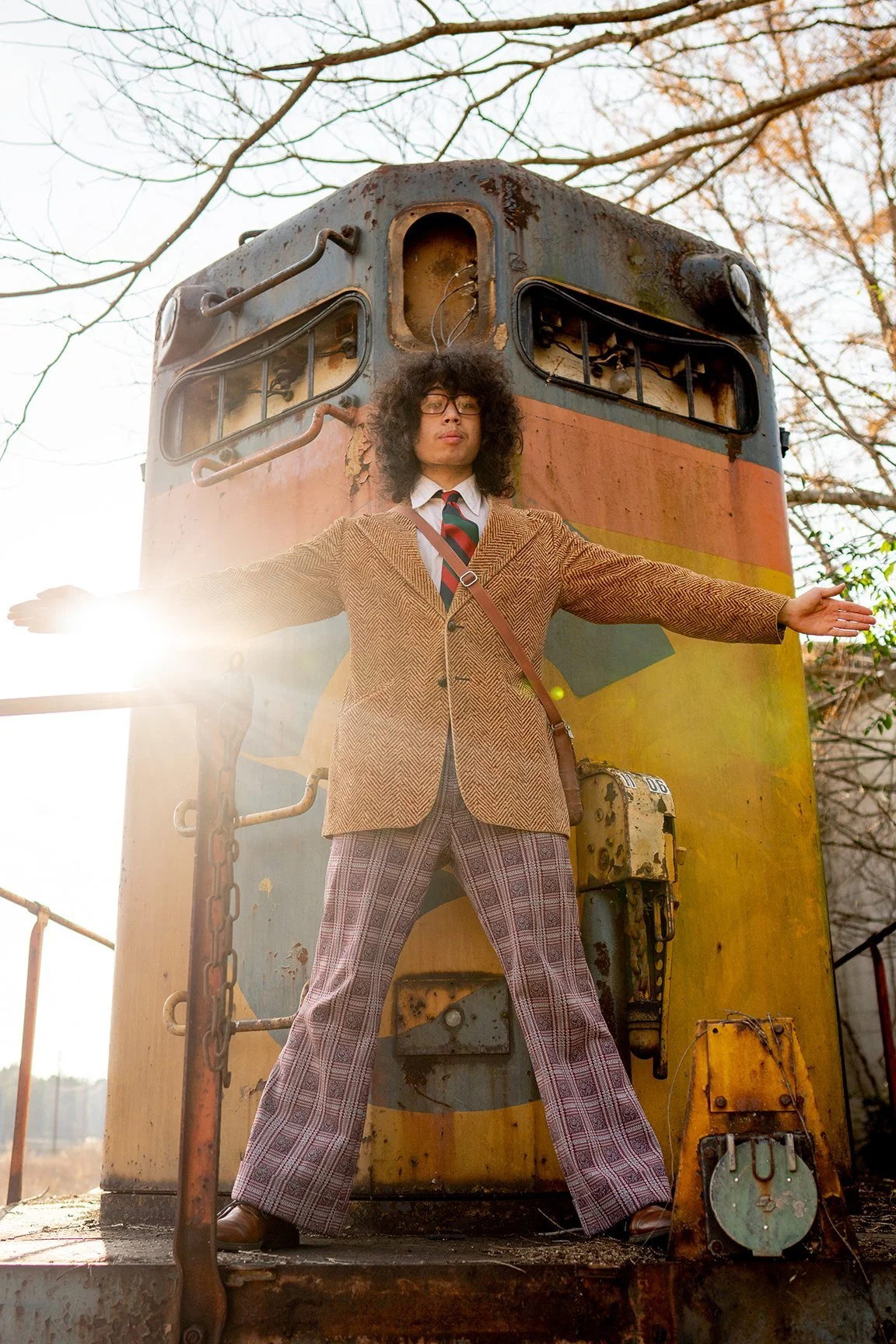

I first became aware of Oliver when we’d see him walking to high school and his style was amazing. I used a little magic to try to recreate that image of him I’d seen on those drives to school.

She He He and I had a great idea for a band photo shot down by the Bulldog Inn but was at least able to catch a shot of the pool.

Athens newest Broadway Star. Since we did these portraits in the studio last sprint Tabitha has gone on to be in Dolly Parton’s biographical musical where she played Dolly’s childhood best friend and she’s currently staring in Ragtime at the Lincoln Center.

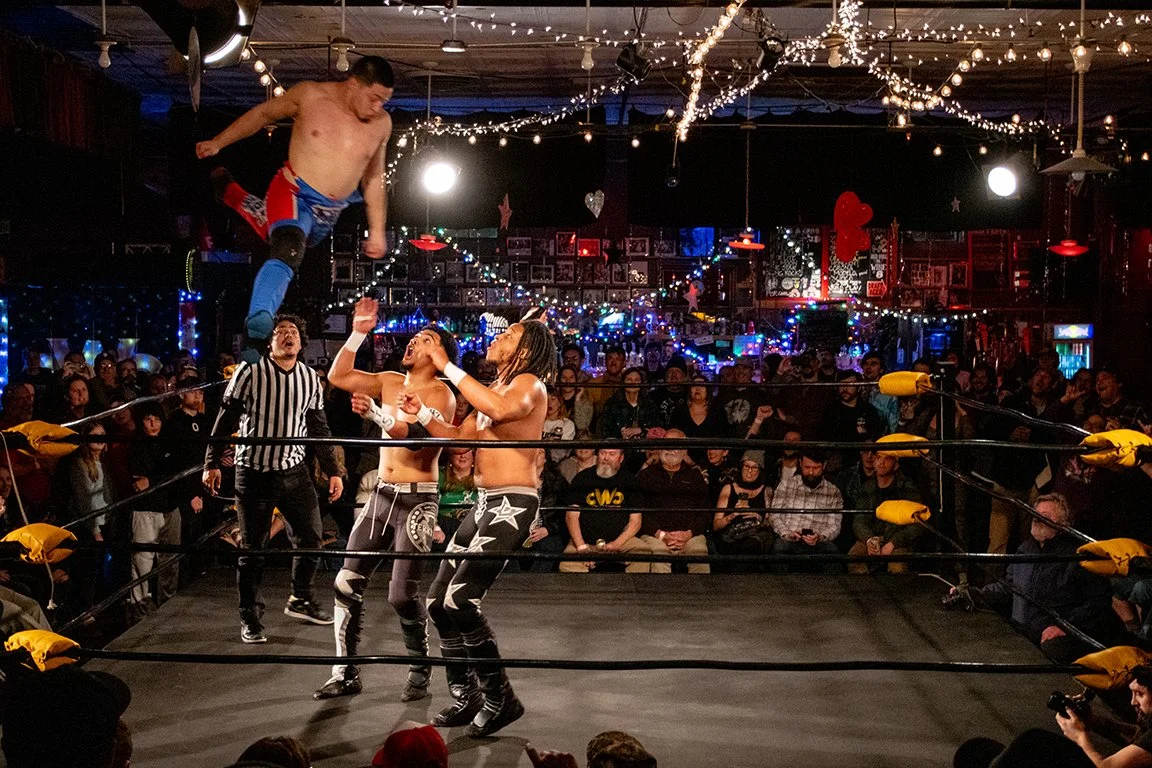

My buddy Cole Taylor knows how to put on a show. The CCW at the 40 Watt Club is really not to be missed.

We’ll see you at The 40 Watt for the CCW on New Years Eve.

Along with Athens House Party I also restarted another project called Southern Eccentrics and had the chance to photograph Marion Coleman.

Aidan Jackson was chosen for Athens House Party by Oliver Domingo.

And then Aidan wisely chose his girlfriend Gee Manring.

Gee Manring for Athens House Party.

Gwen O’Looney was chosen for Southern Eccentrics by Marion Coleman.

Sometime you catch a Big Fish.

Honeypuppy for Flagpole We shot about 5 photos before we were kicked out of the Laundry Mat. I hope they stock Flagpole there.

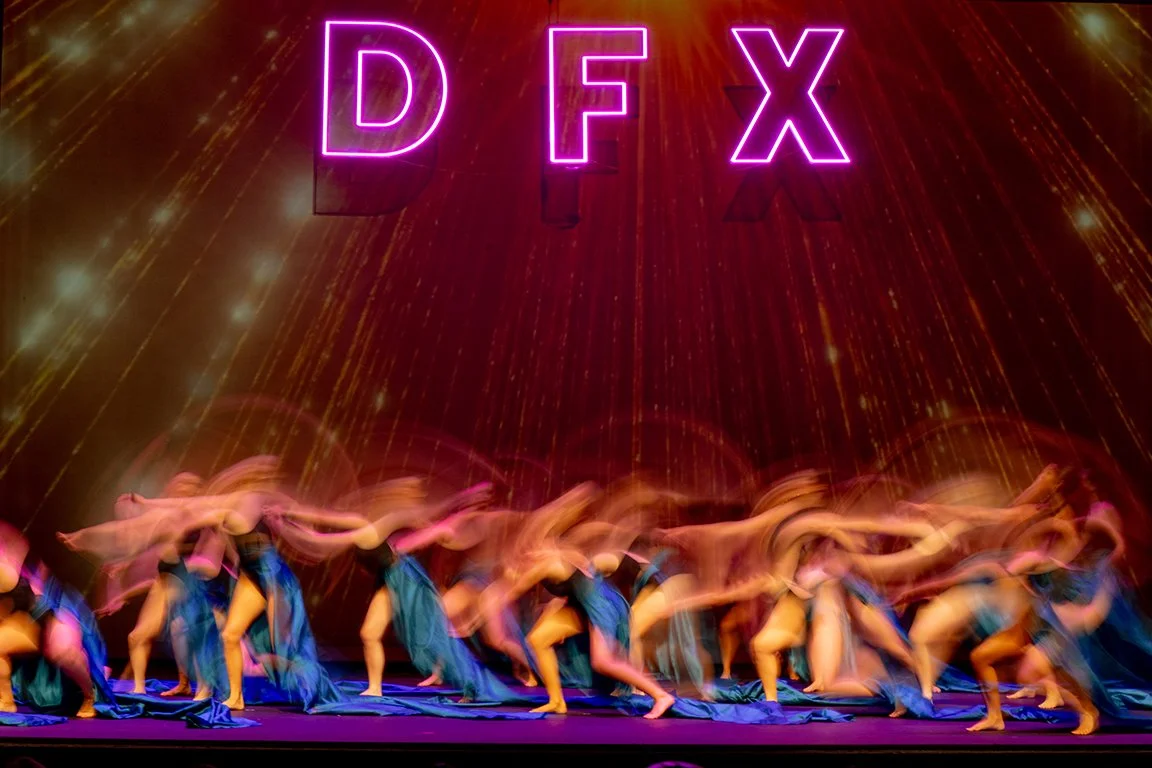

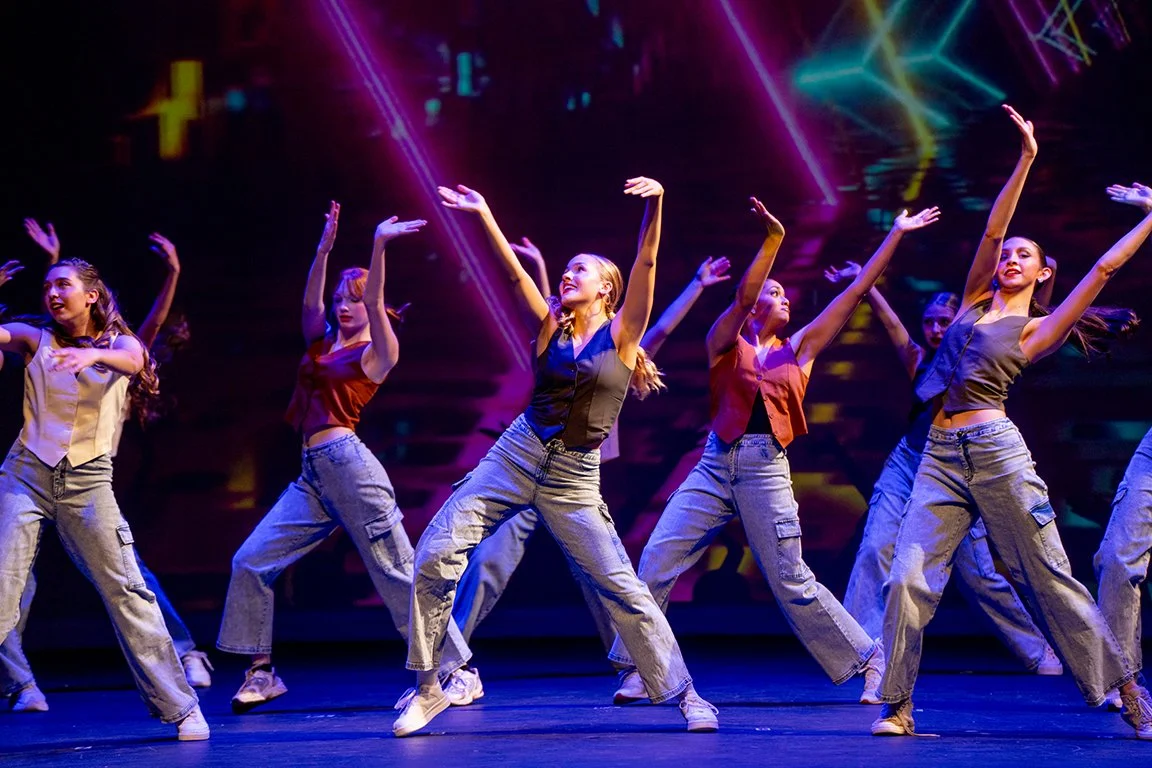

Watching Josie dance with her crew at Dance FX is always amazing and one of the highlights of any year.

There’s not much I love more than watching Josie Dance. Here she is with her company at the DanceFX Spring Show.

Athens Potluck installation at the new Arena at the Classic Center. We’re making plans to have an Athens Potluck event at a Rock Lobsters game in March.

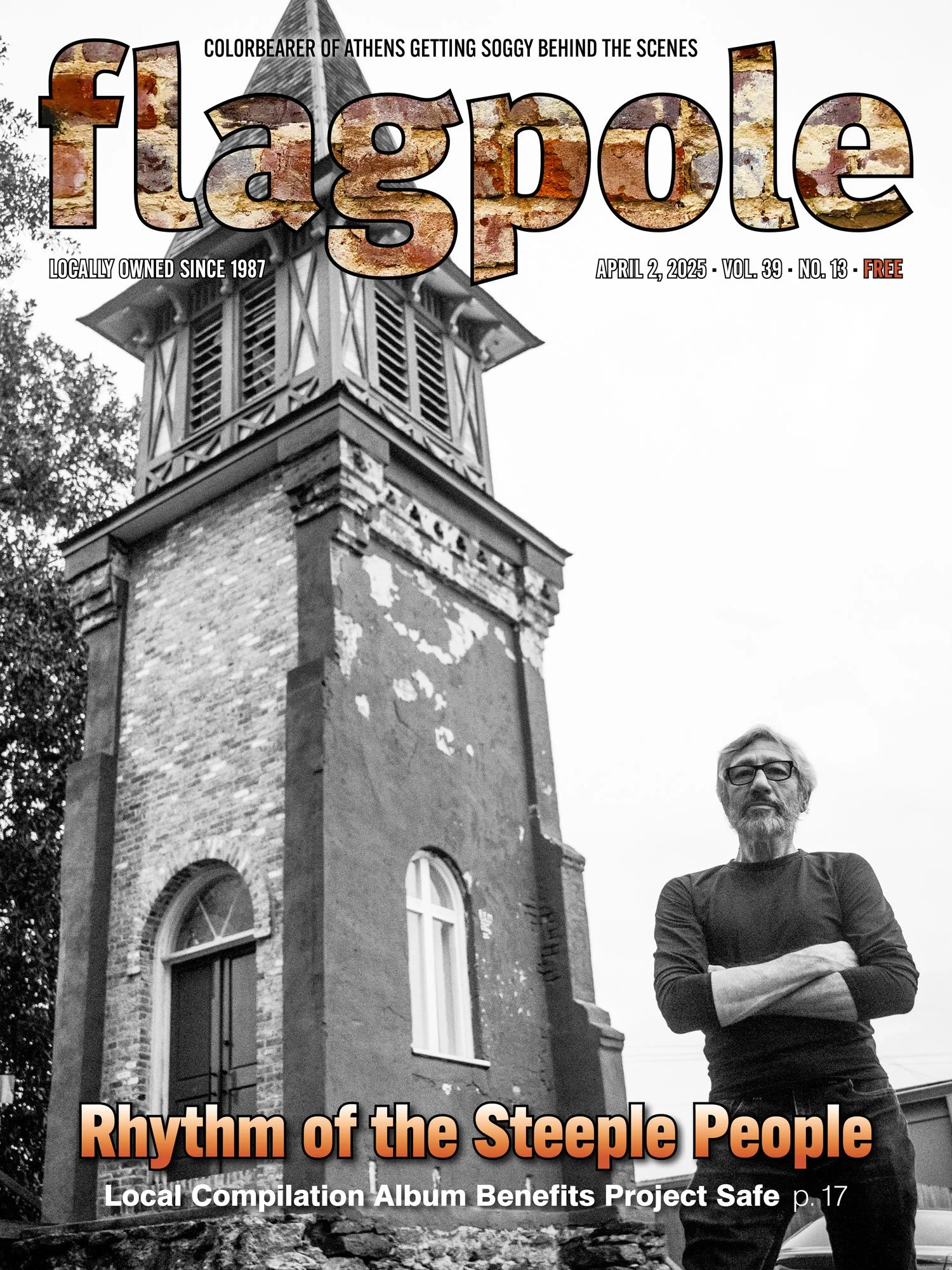

Eddie Glikin on the Flagpole for his wonderful album and project Rhythm of the Steeple People.

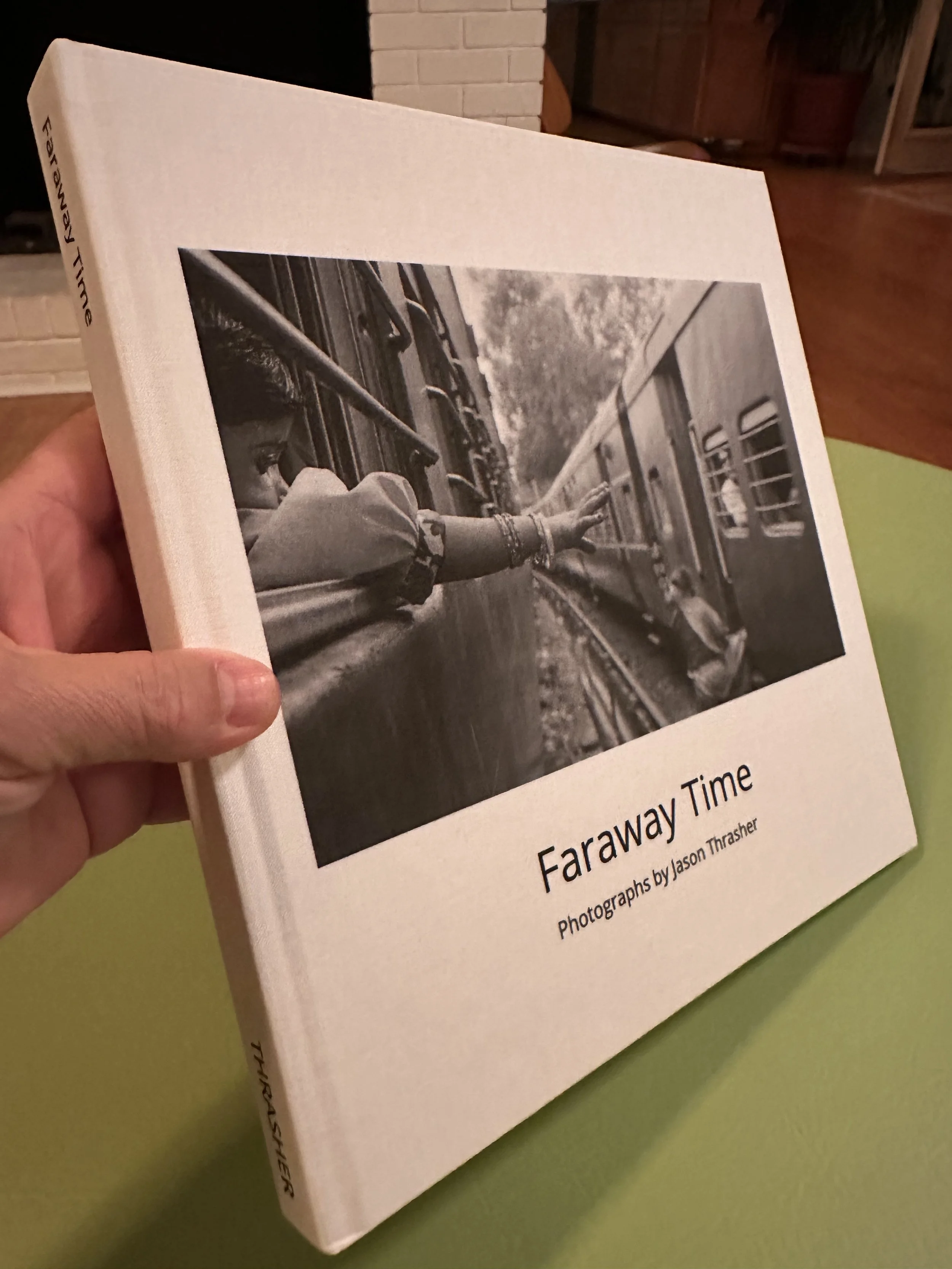

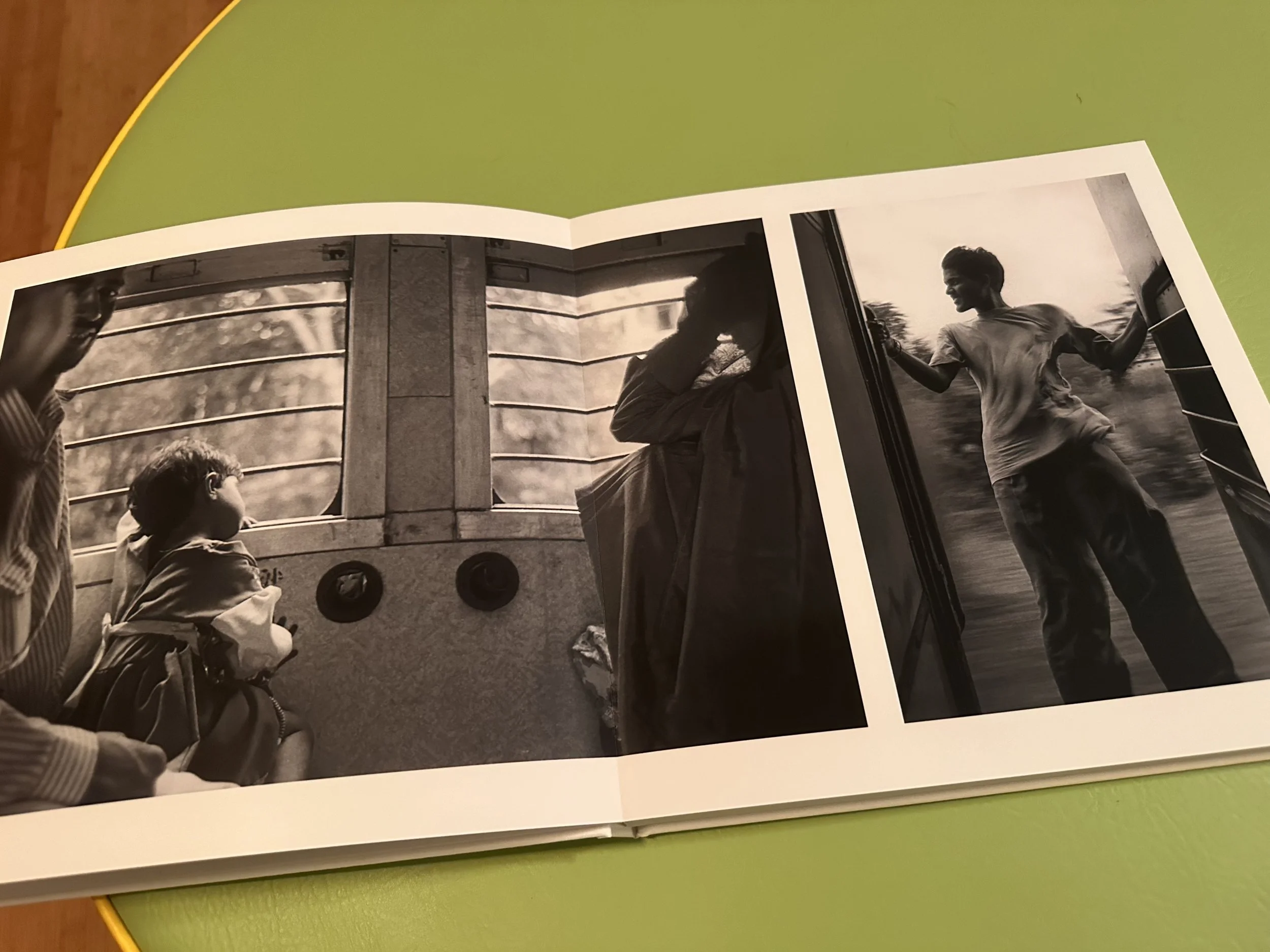

My friend Charlie Friedlander commissioned this one of a kind book of my 1998 India photographs. This turned out so nice. I would love to see it officially produced one day.

Harold Rittenberry was chosen for Southern Eccentrics by Gwen O’Looney. Harold has so many amazing stories and has lived a truly amazing life.

Harold Rittenberry for Southern Eccentrics.

Harold Rittenberry with one of his paitings for Southern Eccentrics.

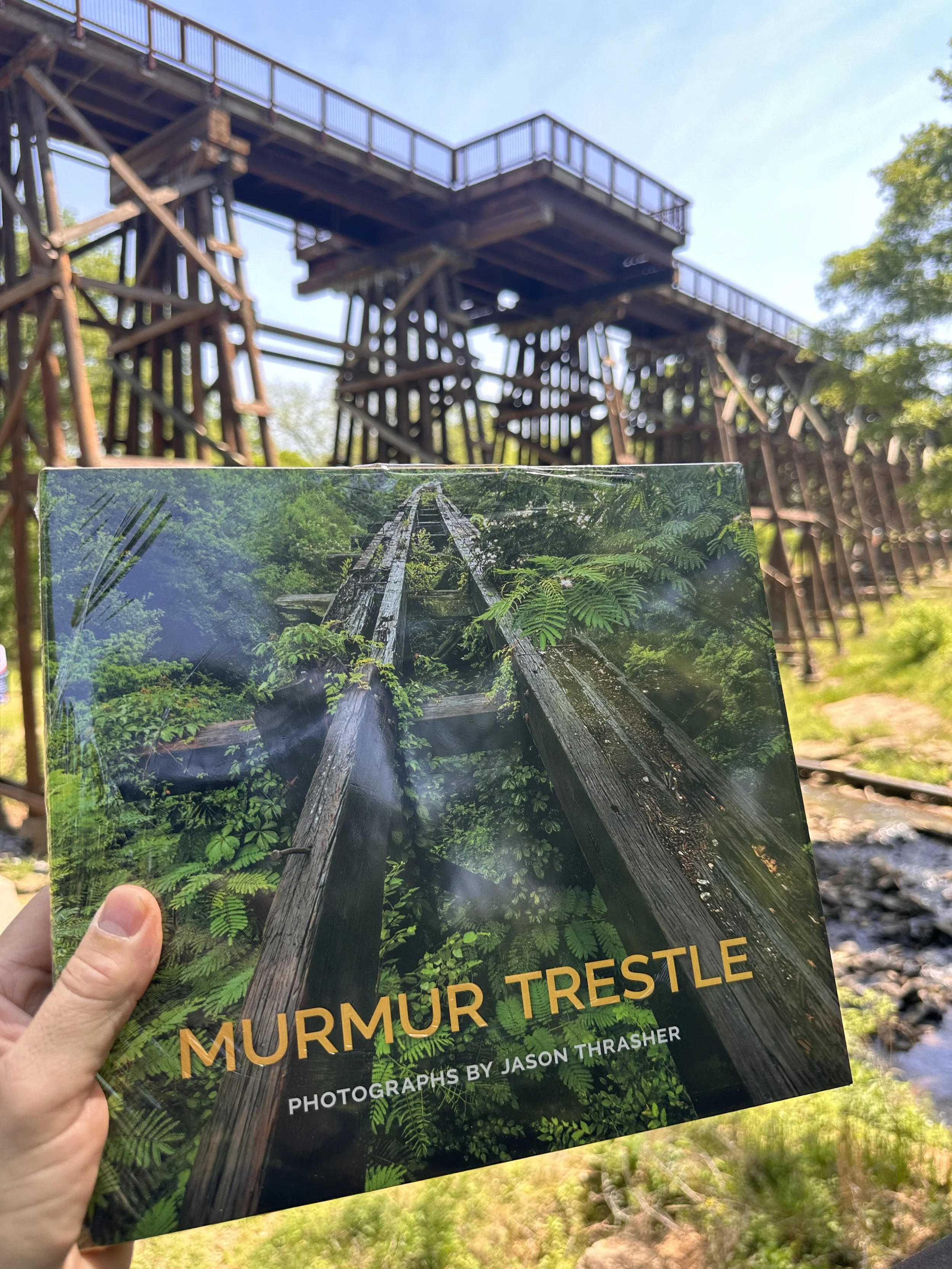

It was pretty sweet running into Peter Buck at the Firefly Trail / Murmur Trestle dedication ceremony.

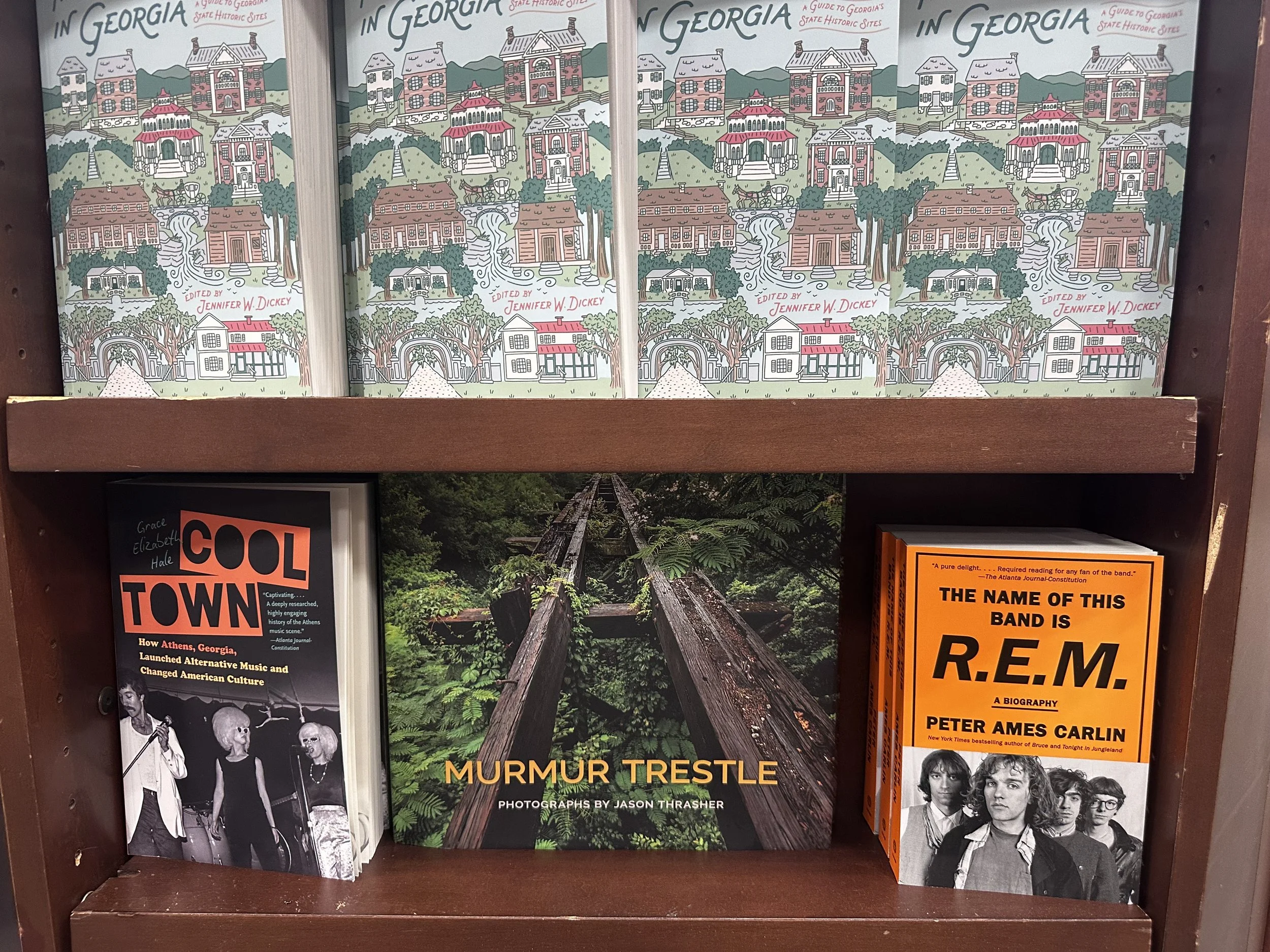

I love seeing the book available around town. You can find it at Nest, Avid, the Georgia Museum of Art and at Barnes and Noble.

Huge shout out to Corwin Weik for everything he does for the skate scene and for the Skate Part of Athens. The 20th Birthday Party he hosted for SPOA was one of the best days of the year and a huge success.

The Skate Park of Athens 20th Birthday Celebration.

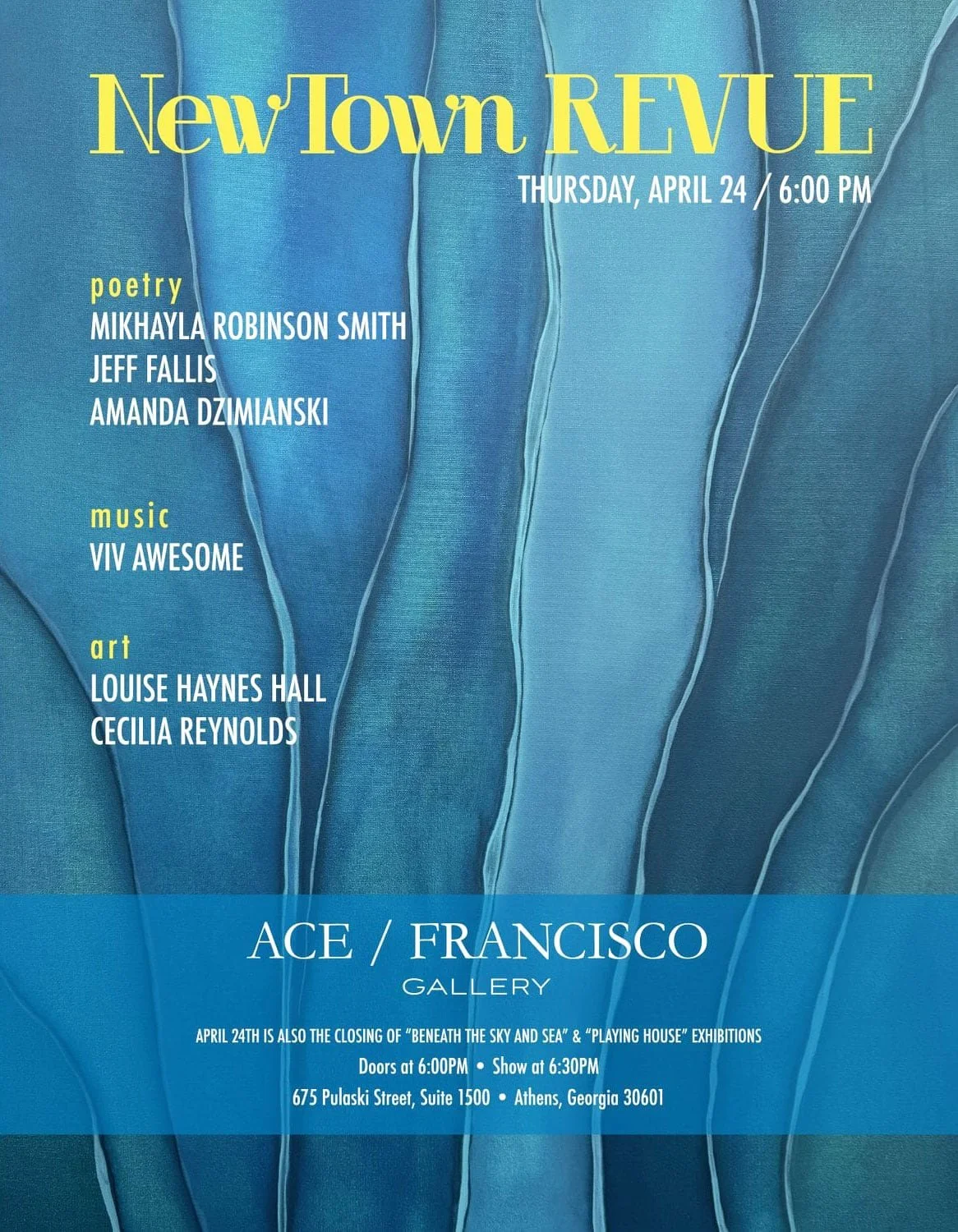

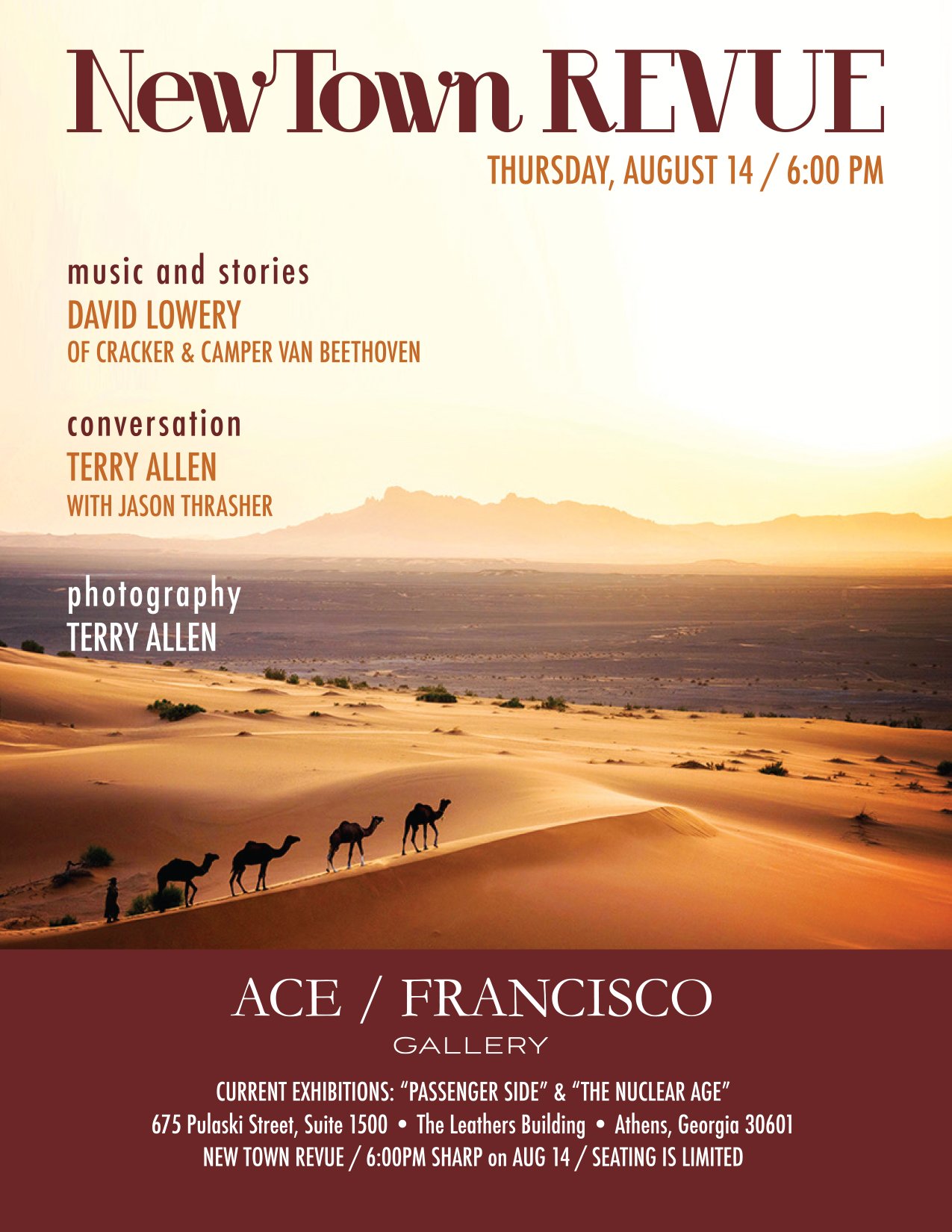

2025 marked the return of the New Town Revue by Beth Hall Thrasher, Deirdre Sugiuchi and Al Dixon.

Made the trip up to the North Georgia Mountains to photograph Old Know Beverage Co for Magnolia’s and Moonshine magazine.

Spring on the Middle Oconee River.

Ritika in the studio celebrating her win as the Vic Chesnutt Songwriter of the Year.

Alligators on Tybee Island.

Senior photos for a lot of hip Athens kids including our neighbor Kai.

Summer on the Middle Oconee River.

The Braselton Public Library for Arcollab.

Made the trip to Savannah to document the renovation of the Savannah City Hall for Arcollab.

Savannah City Hall

Lot of walks with Bob and Tiny. These guys are legends with the kids in the neighborhood.

Lots of play with the new Fuji x100V.

Trembling Earth Orchestra out at Sandy Creek Nature Center.

My first 4x5 Landscape Photo at The Clay Pit.

Kai with the Bunnies.

PCB with the Fuji x100V.

These amazing young adults at PCB.

Author Aruni Kashyap in The Studio.

Keith Bennett and Mike Landers at The Ace / Francisco Gallery kicked off a very busy season of shows at the gallery.

The Kate Morressey Band at Hidden Gem.

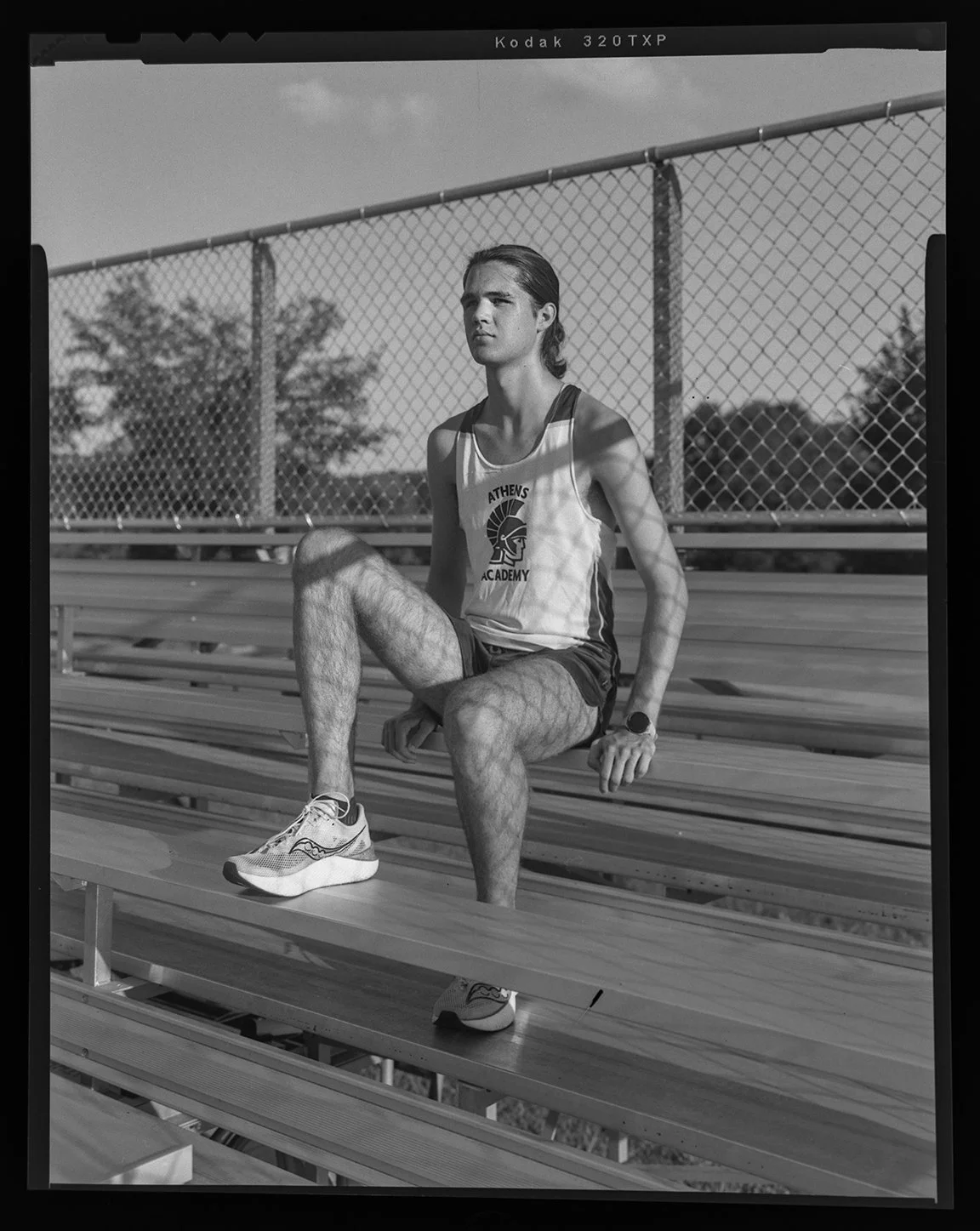

4x5 Senior Portrait of Bryce out at the Athens Academy Track. This kid is fast.

Summer on the Middle Oconee River.

The legend John Fernandes in The Studio.

The Fernandes, Peterson, Russell Trio in The Studio.

Had the chance to photograph some events at OCAF.

Hog Eyed Man in The Studio.

Kristeen Potter for the Lamar Dodd School of Art.

Had the honor of photographing my niece Baily (Right) and her wife Lauren’s wedding in Athens Alabama.

Danielle Rusk in The Studio.

Oconee Joe ready to paddle in The Studio.

Viv and The Things in The Studio.

Hazel of The Things in The Studio.

Sid of The Things in The Studio.

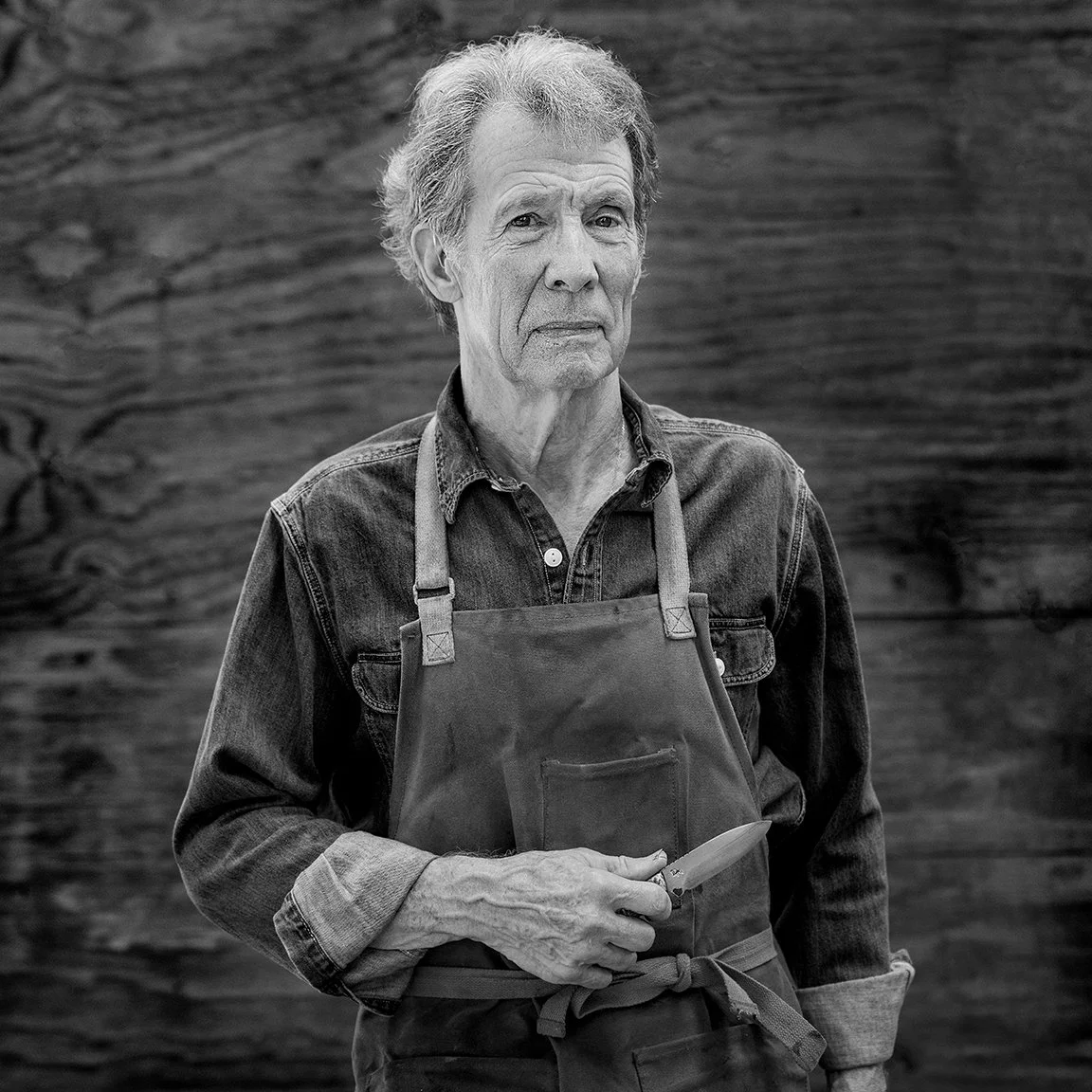

Dan Moye of Cattle Dog Forge with one of his hand made knives.

Anne Boston Richmond of the Swimming Pool Q’s for her new solo album.

Deirdre Sugiuchi in The Studio.

Don Chambers in The Studio.

Quinton Nash in The Studio.

Emma and Trey’s wedding in Madison Georgia.

Frances is now assisting me on photo shoots and she caught this amazing shot at her first wedding.

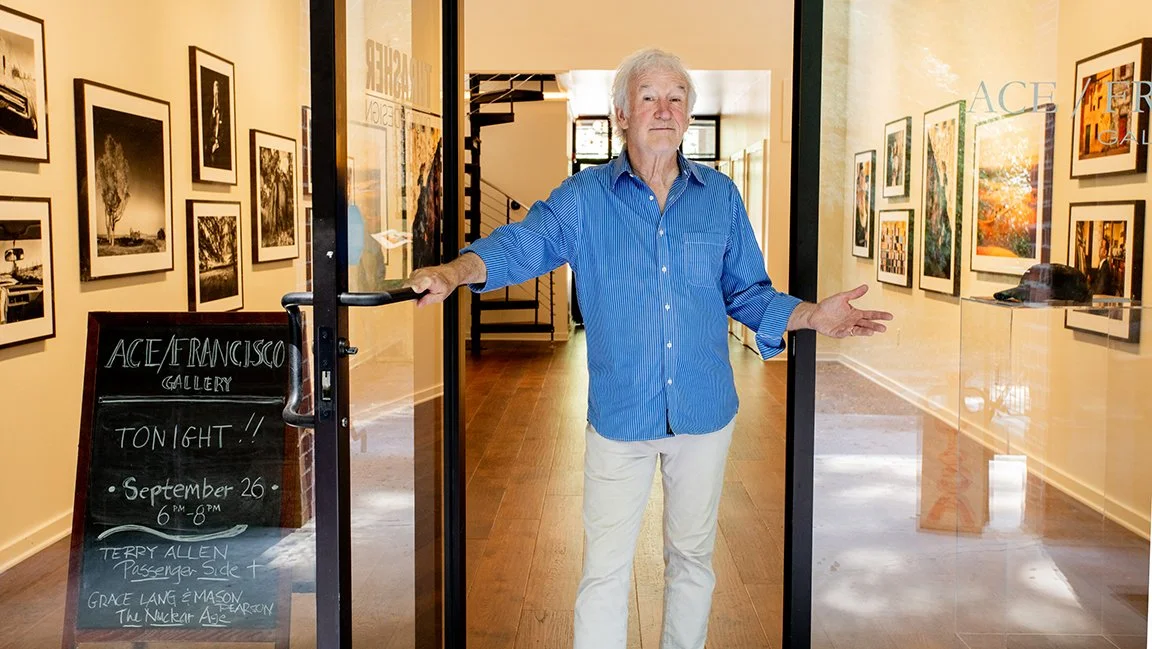

Terry Allen’s Exhibition Passenger Side at The Ace / Francisco Gallery.

Portraits of Forbidden Fruit Tattoo artist at The Studio.

One of many great shoots with scientist at University of Georgia.

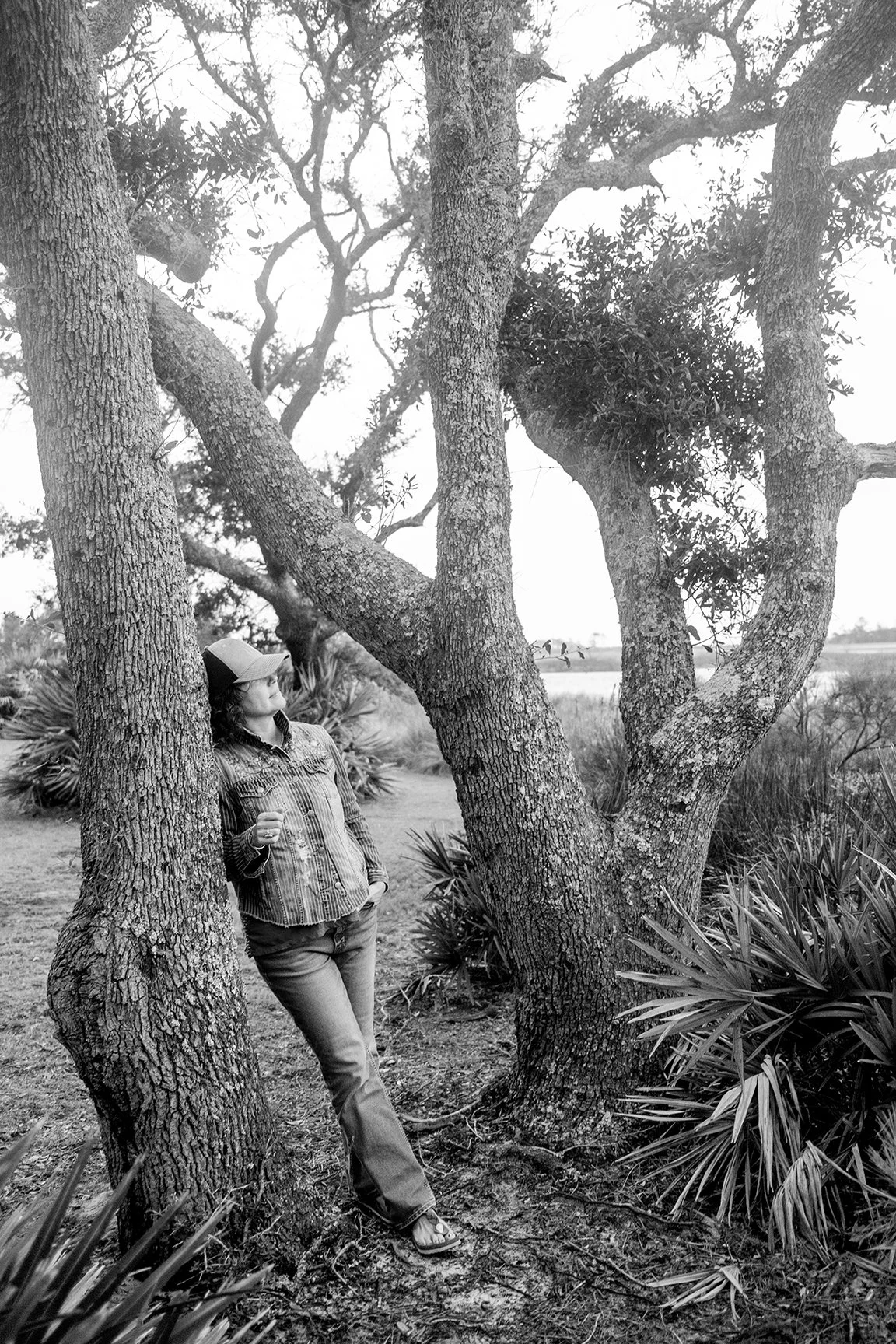

We had the chance to finally visit Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Beth in her happy place, Coastal Georgia.

Alex and Kyle’s wedding on Sapelo Island was beyond beautiful.

Alex and Kyle on the Sapelo Island Watch tower.

Frances Thrasher with her paintings for The Uncanny Valley.

Frances’s Exhibition The Uncanny Valley at the Ace / Francisco Gallery. All but a few of her paintings have sold.

Frances on the cover of her first Flagpole.

I was lucky to catch this rainbow over the Middle Oconee River.

Musician Jonathan Niday.

Jonanthan Niday

Eric Bachmann for his new Crooked Fingers Album.

Eric Bachmann

John Cleaveland for Lake Oconee Magazine.

Adam and Josie for Athens House Party.

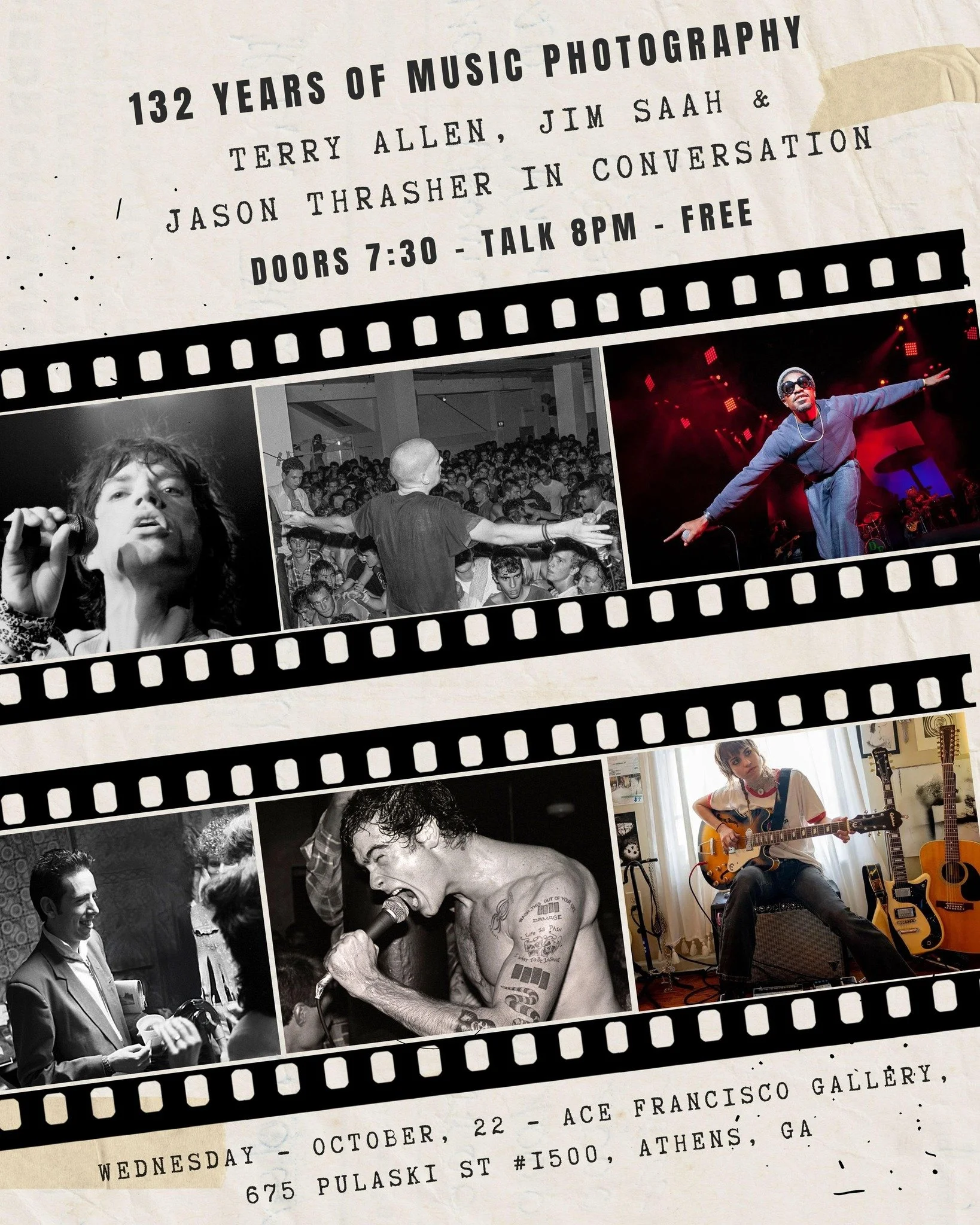

Terry Allen and I hosted our friend Jim Saah from DC at the gallery for a conversation about music photography.

Exactly 25 Years at Teotihuacan near Mexico City.

The Deigo Rivera mural Man at the Crossroads at the Palace of Fine Arts was really more amazing than I could have expected.

Hot Air Balloon ride over Teotihuacan near Mexico City.

Guillermo Kahlo’s darkroom where Frida Kahlo first learned about art.

With Frances at Lowe Mill in Huntsville Alabama where we hung three exhibitions that are on view till the end of Feb.

Rachel Hayes installation photos for the Georgia Museum of Art.

The Pilvinsky Family in The Studio.

Gee Manring chose Josie Callahan for Athens House Party so we went thrifting for the photo shoot.

Frances sold out this wall at her show at Ace / Francisco. Only 4 more paints are available.

I really could not be more proud of my girls. Seeing Josie dance in the DanceFX Winter Show was a truly wonderful experience.

Frances delivering her artist talk at Lowe Mill in Huntsville Alabama.

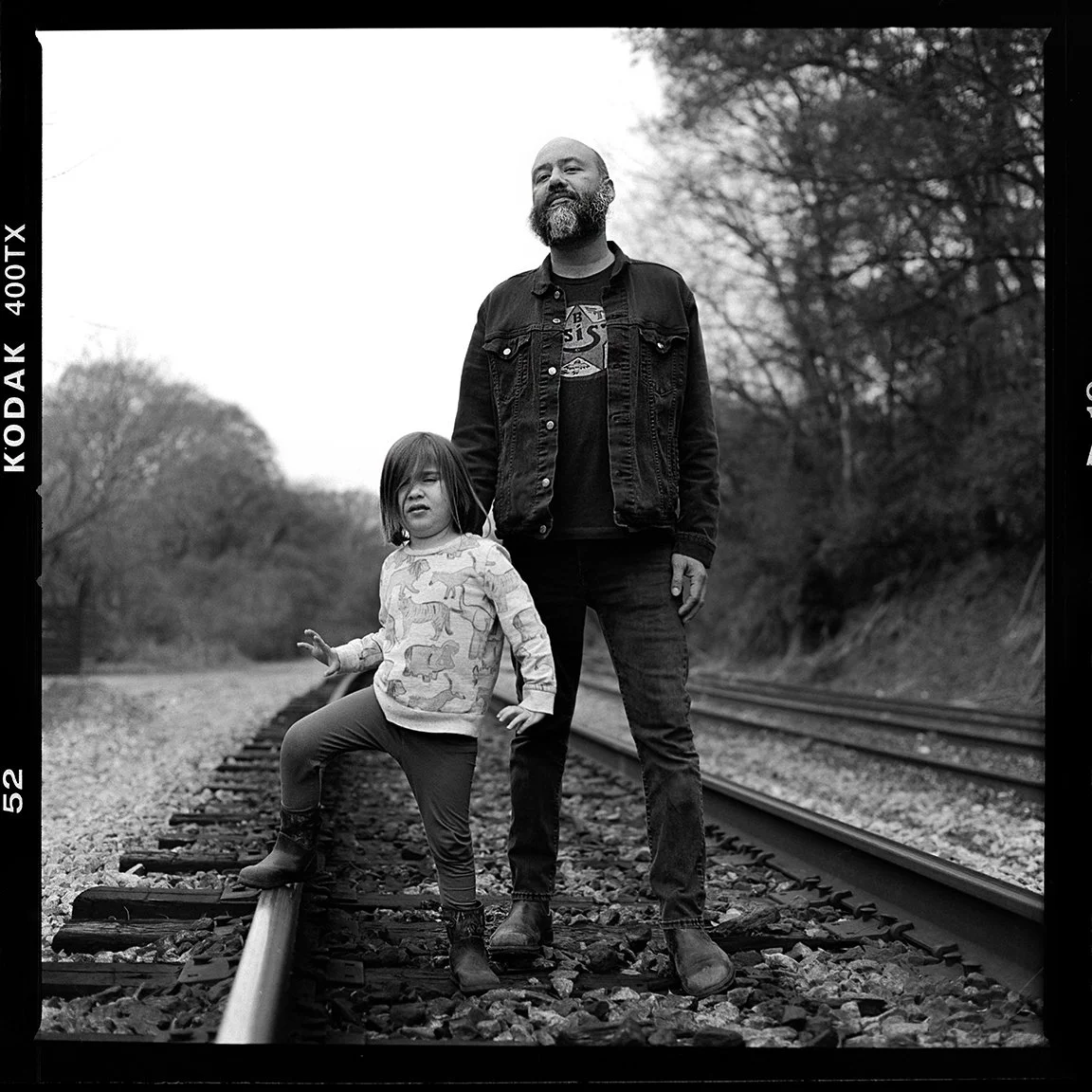

Finished the year playing with a new old camera and BW film. May 2026 will be the year of the Hasselblad.

Jim and Leo on the tracks by the studio.

Frances and Josie one year later in the same spot at the 4×5 photo but not shot on the 6×6 Hasselblad.

Sapelo Island and The Alligator Pond

Sapelo Island and The Alligator Pond

The Bell Hotel

The Bell Hotel - The 1916 downtown Athens building reborn as boutique hotel.

Following a two-year renovation, a commercial building at 183 West Clayton St. has been reborn as The Bell Hotel, an elegantly hip property being marketed as a “historic jewel” and celebration of art, architecture, and “timeless sophistication” in the heart of downtown. The project’s grand opening was held Tuesday.

The three-story building, situated about a block from University of Georgia’s campus, was constructed in 1916 to house advanced telephone equipment for the Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Co. (thus, the hotel name). The telephone company departed in 1966, and an era of private commercial use stretched across ensuing decades.

Atlanta-based developer Brad Foster, philanthropist Marie Brumley Foster, and their sons began work on the 108-year-old property in 2022. Working with preservationists, the restoration efforts discovered original design plans for the building by architect P. Thornton Marye, noted for his Moorish-style blueprints for Atlanta’s Fox Theatre, which opened 13 years after the Athens building.

Athens-based architectural firm Arcollab aimed to carefully restore the property while also transforming it, bringing the yellow-brick façade and terra-cotta detailing “to its former glory, reflecting the craftsmanship and grandeur of its era,” per project officials.

As boutique hotels go, this one’s very boutique, with just eight guest rooms (each with unique designs), plus a four-bedroom suite. One key addition was a rooftop terrace with panoramic downtown Athens views; that was possible because the century-old building’s reinforced concrete, post-and-beam structure remained robust, per officials.

Other design highlights include a parlor-style lobby, a centerpiece grand staircase, and what’s described as statement lighting, chic furnishings, and a bevy of curated art, as selected by interior design firms Simplicity: A Southern Lifestyle and Seiber Design.

Classic City Wrestling and the Drive-By Truckers

Classic City Wrestling and the Drive-By Truckers at the Fabulous 40 Watt Club

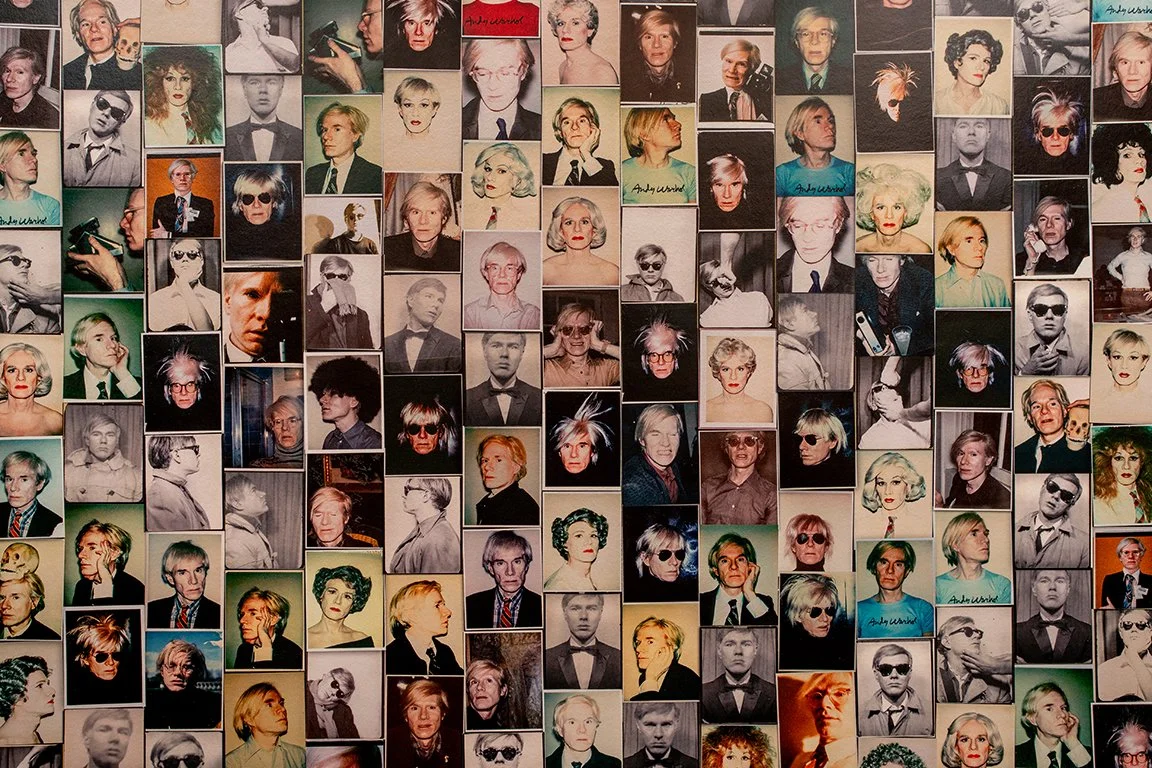

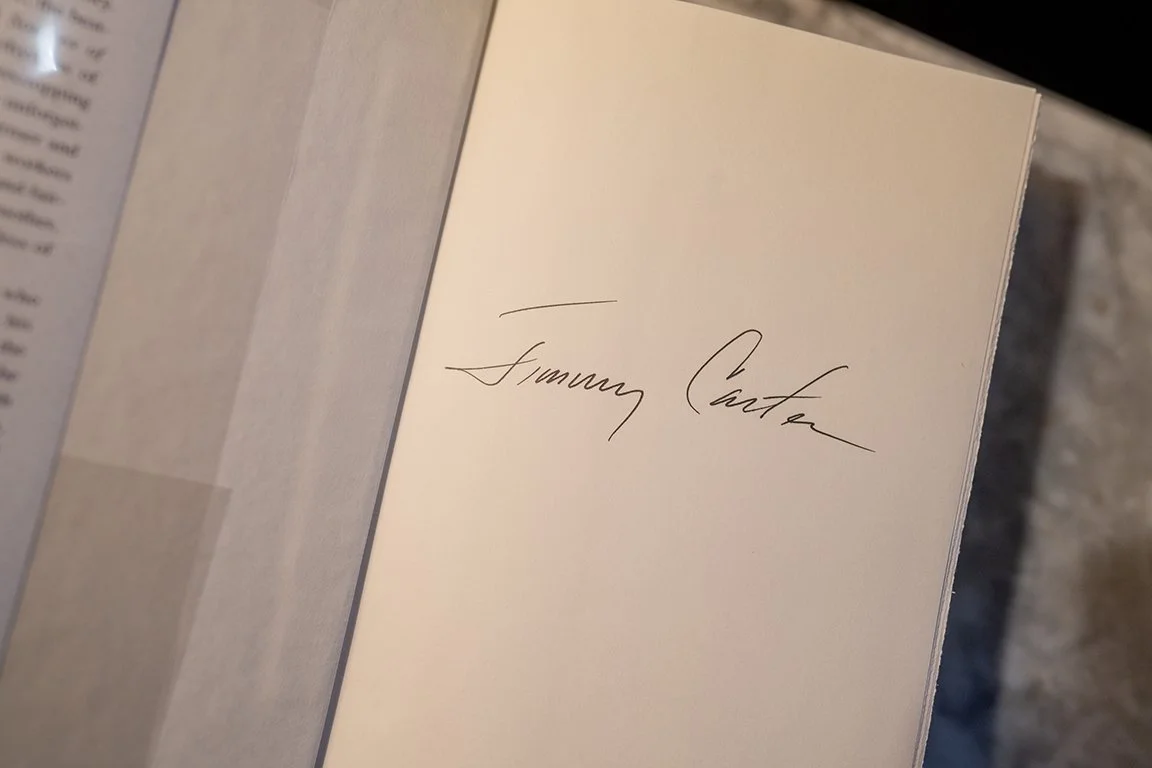

John Cleaveland - The Jimmy Carter Landscape

John Cleaveland - The Jimmy Carter Landscape

John Cleaveland, Jimmy Carter, and Southern Landscape that Connects Us All

Story by Russell Worth Parker / Photography by Jason Thrasher - Originally Published in Garden & Gun

John Cleaveland never meant to be an artist when he left Jacksonville, Florida in 1980, planning to study forestry at the University of Georgia. For a “total redneck [who] loved the woods and being outside,” forestry made a lot of sense. But when Cleaveland arrived, Athens, Georgia, was experiencing an intoxicating moment. The B-52s were touring the nation after their cocktail-fueled birth during a 1976 jam session. R.E.M. was playing house parties, still three years away from their debut album, Murmur. The first Georgian to lead the nation was in his last few months in the Oval Office. Things were in motion, a gentle riot of light and color and sound.

Today, a visitor to Athens pays $25 to walk amongst chain stores following a guided music history tour. But Cleaveland’s Athens meant immersion in a DIY movement born of humidity-swollen nights and dawn’s mist clinging to kudzu fields, of ramshackle rental houses redolent of cheap beer and dance-fueled sweat, and artists who rode a creative flood into a formerly quiet, quirky town, seeking cheap living and inspiration.

After a few semesters spent thinking about pine forest basal layers and the application of fire to the southern landscape, Cleaveland took an art appreciation class for non-art majors taught by a sculptor named Bill Squires. Squires allowed his two hundred students to either write an essay or fill a sketchbook. Cleaveland, troubled by dyslexia, filled two. When he returned them, Squires said, “I need to talk to you.” Eventually dissuaded of the notion that Cleaveland was an art student padding his GPA, Squires said, “You know, John, I have never had anybody turn in anything like this. You should take some drawing classes. You've got some talent.”

Turning away from forestry, Cleaveland set his sights on becoming a graphic designer, figuring that even in Athens’ early-80s party-to-party atmosphere he had to make a living. There was but a single problem, “I couldn't get into graphic design school.” But by then, Cleaveland was beginning to understand that life is not linear, that, often, one should listen to what the landscape is telling you. “One of my teachers was Herb Creasy, a wild man abstract expressionist. I was in his color theory class, and he heard me talking about it and said, ‘Cleveland, they don't want you in that f*cking school. You can't follow directions for shit. You never do what the project's supposed to be. But that's not a bad thing. You should take my painting class next quarter.’ And the first day of his class, it was like, ‘Oh, here's what I'm good at!’”

What Cleaveland is good at has evolved over the intervening four decades, leaving a legacy on permanent display in fine art institutions like the Asheville [NC] Art Museum, the National Museum of the Marine Corps, and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia. His landscapes also hang in private and corporate art collections in places like the 3M Company, Bessemer Trust, and the Alabama Power Company. But the work and place that may best explain Cleaveland is a pair of 4’ x 8’ landscapes, expansive contemplations of the Broad River and a Georgia hillside respectively, hanging in the University of Georgia’s State Botanical Garden of Georgia, a place built to “be a garden that celebrates the best in southern horticulture, natural heritage, and culture through excellence in gardening displays and practices and stewardship of healthy natural ecosystems.”

Cleaveland’s work residing in the Botanical Garden’s ecosphere reflects his artistic purpose. “My point has been, since I was 26 and finally found what I was supposed to paint, landscapes in Georgia, was to find the beauty in the common, in what's around me, and in what's worth paying attention to. I'm able to grab it at a time and stop it. I'm painting to engage you in a nostalgic endeavor, which is not looking back at something with rosy glasses, but making you want to be there; to feel the things evoked. I'm evoking home. I'm evoking slow. I'm evoking nature. They're all connected.” Now that connection has all come together at The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, in a new show entitled The Nature of the Man: Landscapes from the Childhood of Jimmy Carter timed to coincide with President Carter’s 100th birthday.

Standing in Cleaveland’s Farmington, Georgia home and studio, formerly the tiny community’s general store, pool hall, and post office, looking at the twenty-one paintings meant to tell the story of Carter’s boyhood in Sumter County, Georgia, I feel everything Cleaveland means to evoke while also furthering his mission to reveal the connections we all share with, and through, the land around us. The images are sufficiently realistic to be visceral while not so hyper-realistic as to feel cold or calculated. His work is alive. I hear the water in the creek. I feel the barefoot chill of sand on a Georgia creekbank. I smell freshly turned dirt on the breeze giving life to the curtains in a farmhouse window. They are things I know, things I have lived.

The work, as Cleaveland intends, stands alone. But for the show, each painting will have a QR code next to it that will, once scanned, allow the viewer to listen to Jimmy Carter read portions of An Hour Before Daylight related to, or inspirational of, the specific work they are viewing. For Cleaveland, “It's a way of paying homage. I'm no hero worshiper, but as far as people who are up on a plane of what they've done with their life and the stands they've made that are admirable, Jimmy's a North Star. He wanted to get ahead environmentally of where we're at, and where we're at now sucks. And if we had been doing some of the things he wanted and knew we needed to do, we'd be in a better place. Talk about somebody with foresight, Georgia's rivers are in the shape they're in because he was governor. Because he chose to say, ‘We're going to do this’. And when you go down to the coast, there are islands that aren't developed because, as a governor, he worked with the people that were down there and said, ‘We want to save these things, how can we do it?’”

As much as The Nature of the Man honors President Jimmy Carter, the show is also intensely personal. Cleaveland’s son Atticus, a kind boy on the precipice of manhood and deeply focused on the environmental state of the South, took his own life on November 4, 2020. Cleaveland wears the pain of that loss just beneath the surface of a face deeply lined by years and elements. With his rangy frame muscled from chopping and stacking firewood in artistically arranged piles for the business he maintains when he is not painting away the darker hours of the day, his is a masculine energy. But to ask him how much of the show is about Atticus, the son with whom Cleaveland read An Hour Before Daylight multiple times, is to invite immediate tears from closed eyes and a response choked through a fist-covered mouth, “All of it.”

If the paintings in the show express Jimmy Carter’s love of the land, they speak wordless volumes about Cleaveland’s love for his child and the land through which they are still connected. Even more pointedly, it celebrates the connection with Atticus that Cleaveland built through Carter’s story. As Cleaveland says, “This beautiful man, he's talking about growing up in this hard place, but he loves it so. You get in the book that his father was not an emotional man, and Jimmy just worshiped the ground he walked on. And that's why, when his father was dying, he came back to Plains and changed his trajectory in life, realizing ‘I'm needed here in this community.’ I read that book when Atticus was little, about Jimmy Carter growing up in this place that didn't exist anymore, and I cried at parts of it. I've got a photograph of Atticus down there in Plains the last time Jimmy taught Sunday school. Atticus got to hear him. I thought that it was a great gift. And then a couple of years ago, I thought, I have all these images from the times I read that book. A lot of people don't have a visual image of what Jimmy is saying to them about standing in this creek, fishing with his father with a stringer tied to his belt loop. They don't know what that feels like. They don't even know what the place would look like.”

“The Nature of the Man” Opens at the Carter Center Presidential Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, on December 14, 2024, and runs through March 31, 2025. There will be a reception open to the public at 4:00 pm on the first day of the show, of which Cleaveland is clear, “Anybody can show up because it's the Carter Center. The idea is food that is pure hospitality, stuff you might find on the table at the church. Paper plates and metal flatware, no single-use plastics because let's be hospitable, but also be conscious of what we're doing.” It's an approach that celebrates both Carter and the paintings that celebrate his boyhood, of which Cleaveland says, “We say it ‘speaks to you’, but it's not speaking to you. It's just an invitation to turn off all the other noise.”

UGA Dance Dept

Photographs for The Young Choreographers Series - Chaos Theory